be offended, be very offended ...

Against this fear, art is fresh healing and fresh pain.

Jeanette Winterson, Art Objects

Why are images increasingly confused with reality? The real has assumed greater significance in contemporary art over the past few decades. However, the real, as it is represented in art’s critical engagement with social issues, is never complete, but rather often cynical and ambiguous. Reflecting on two recent ‘art controversies’, Australia Council funding for a new media art project Escape from Woomera1 and the furore over Telstra National Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Art Award winner Richard Bell’s t-shirt text, it’s apparent that the image is caught in a trap of literalism. In sharpening our senses for moral conflict, these artists and artworks have been singled out for censure in which virtuality has been confused with reality.

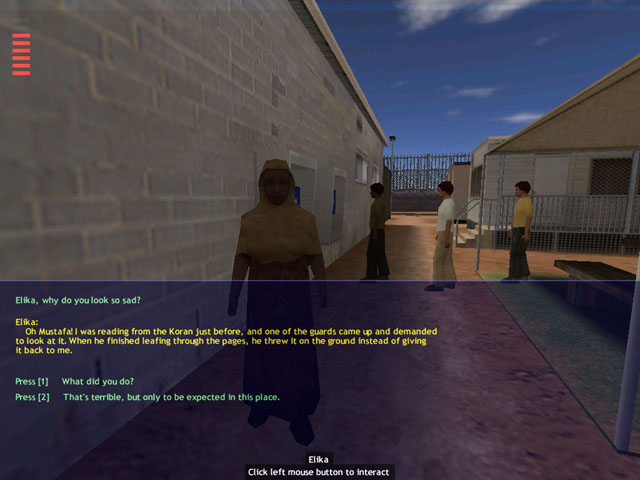

Steven C. Dublin argues “two elements are required for art controversies to erupt: there must be a sense that values have been threatened, and power must be mobilised in response to do something about it”.2 Those mobilisations can include governmental attempts to regulate symbolic expression. The media plays a large part in fuelling these controversies and this essay canvasses the reporting of the Bell and Escape from Woomera incidents. Woomera lasted a mere few days, but ‘white girls’ kicked on for several weeks. The Sydney Morning Herald newspaper broke the Escape from Woomera news as a front page story.3 Then Minister for Immigration, Phillip Ruddock, voiced his objection on the basis of the granting of federal funding for an artwork that was critical of the government’s policy on the issue of detention of asylum seekers and refugees. Ruddock also commented that the decision to fund “reflected poorly on the Australia Council”. A ministerial spokesperson confirmed that the Australia Council would be contacted to “express a fairly firm view about the allocation of [its] resources”.4 Arm’s length funding mechanisms, such as the Australia Council, are intended to enhance democratic values and expressions rather than encourage unilateral policy support. Based on peer assessment, the Australia Council art form boards are intended as a forum for decision-making founded on expert view. A representative of the New Media Arts Board reiterated that the project proposal was a sound one with artistic merit.

Later that year, Richard Bell, the first urban Aboriginal artist to win the Telstra Award in its 20 year history, wore a t-shirt to his award ceremony emblazoned with the slogan, “white girls can’t hump”.5 This tabloid-style slogan, ordinarily in Bell's work a tightly wound compression of a seriously burning issue, was also an artwork – an image – and as such further confounded the currency of image. Postmodern irony aside, as a statement, Bell’s text is perplexing and the artist conceded that it was “an absurd thing to say … [but] it’s up to people to look”.6 Most obviously, the text is a reference to the feature film title White Men Can’t Jump, evincing the complex interplay of sexuality, race, power and colonialism. When read literally and in isolation, individual sensitivities might find these words offensive. As a result, some demanded that Bell, now undeserving of his Award, return his prize money, while others demanded a public apology due to the offence caused. How might we account for diverse and contradictory acts of interpretation? In a turbulent and subjective interpretative environment, how can one interpretation be held as the true one? As Bell found himself embroiled in a Fanonian drama of power relations between black man and white woman – although, significantly, Indigenous women also made public statements about Bell’s artwork – surely there is more going on here.

but is it art?

While these scenarios uncomfortably unfolded, the artists and commentators found it necessary to make a distinction between ‘art’ and ‘real life’. For sure, an art object has its own materiality; it is a physical object as well as a representation. The Escape from Woomera artists are clearly sympathetic to the appalling situation of detainees and their work seeks to raise awareness of the conditions in these detention centres. However, a representation of a detainee breaking out of prison or a gamer playing the role of a virtual escapee, is not the same as advocating or committing such actions. Overarching principles in gaming include point of view, role-play and identification. As an artwork, there are aesthetic and narrative imperatives that drive the work. Blast Theory’s Matt Adams said that Escape from Woomera “poses many questions about who we identify with and why when we play games. At the moment, games such as this often attract opprobrium for combining games with serious issues. They are seen as trivialising important political questions. I see this in reverse: they bring a long overdue seriousness to games.”7 This view is significant because one of the grounds for criticising the funding outcome was that a game could not be considered art despite a panel of peers having made that decision.

In Bell’s case, the inscription of the slogan doesn’t make it true. Although, as written words, more authority might be granted them and there was a failure to recognise the text as an artwork. Given the artist’s satirical quizzing of interracial sexual and power relations in his work, the literal reading of the words caused the viewers to overlook ingrained issues of nation, race, violence and gender. Human Rights Commissioner, Pru Goward’s, demand for an apology seemed an act of velleity. In demanding this apology on the basis of an alleged offending breach of community standards and in calling on ‘Aboriginal leaders’ to rebuke Bell, did she appreciate the irony of the Australian government’s refusal to apologise to Indigenous people? Whose offence or standards matter most in this variance? And these are the questions, the double standards, this artwork brought into sharp relief. When whiteness and/or womanhood are imbued with privileged cultural value and virtue, the moral high ground isn’t easily wrested. This equation of whiteness with morality was reinforced when Prime Minister Howard was interviewed on talkback radio and referred to the artwork as “tasteless … I think we should have more taste”.8

Richard Bell wearing his t-shirt artwork at

his Brisbane studio, December 2005.

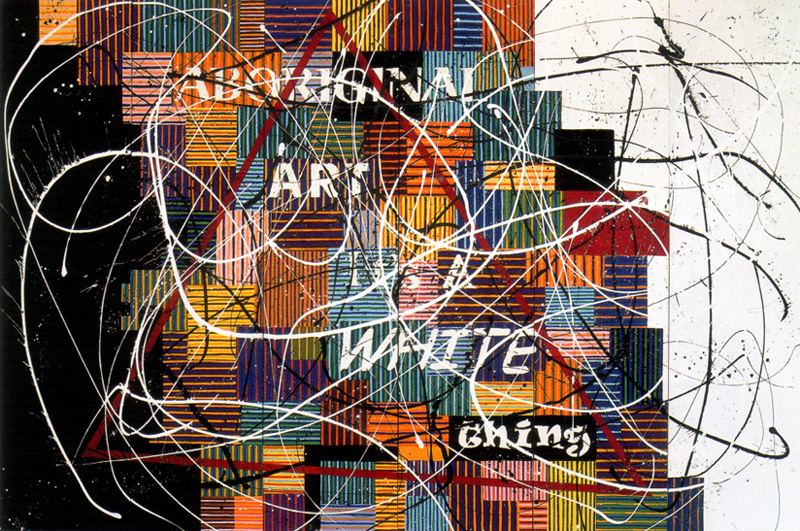

A game about the detention of asylum seekers isn’t simply child’s play; an exercise in wordplay isn’t simply a tasteless pun. Real things are happening here. The realness of art can lie in our reactions to it. And that is the obvious point of these artworks – they cut to the heart of the matter. They construct discomforting questions that challenge any possibility of a ready moral or censorious stance in response to outrageous acts and vividly serious matters. However, in the case of Bell, furore over the t-shirt cast a shadow across his award winning painting and manifesto, Scientia e Metaphysica (Bell’s Theorem), which pointedly critiqued the cultural and financial exploitation of Indigenous artists in the art market with the proclamation that “Aboriginal art – it’s a white thing”. The t-shirt might be seen as a distraction. Even though the panel that decided the Telstra Award was comprised of nationally respected arts experts, t here was another bloated ‘is it art?’ retort when the Australian newspaper’s art critic Susan McCulloch described Bell’s prize-winning work as derivative and outdated, preferring instead a particular kind of ‘Aboriginal’ style and thus playing into the lived reality of Bell’s theorem.9

i am, you are, we are unaustralian

As the federal government considered introducing sedition provisions as part of its anti-terrorism bill (passed into law on 6 December 2005 after debate was gagged), these issues became more pressing. When I initially started thinking about this text, my intention was to write about these artists and their work in the context of current race relations and their implications for nation or nationalism, addressing Joseph Pugliese’s idea of the ‘unAustralian’ as a category of exclusion. Both artists discussed here address issues surrounding the construction of white nationhood, of whiteness as the true expression of Australianness. As Pugliese notes, the accusation of “‘unAustralian’ functions in disciplinary and coercive ways that work to discredit and censor individuals or groups that publicly question and contest government policy.”10 Predicated on an ‘us and them’ mentality, the unAustralian denotes someone who does not conform to the dominant culture. In variously discursive ways, allegations of unAustralian were levelled at Escape from Woomera and Richard Bell. Theirs is an unAustralianness that Pugliese describes as having been adopted with some pride as “signifying a different order of nation – a locus, ironically, ‘excised’ from the nation that enables … an ongoing commitment to a supra-national ethics of welcome, hospitality and non-violence”.11 Escape from Woomera is more readily understood within this frame and together with other artistic acts seeks to create hospitable and liberated spaces for asylum seekers and refugees.

Richard Bell’s 20 th Telstra National Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Art Award winning painting, Scientia e Metaphysica (Bell’s Theorem) or “Aboriginal Art – It’s a White Thing”, 2003. Photo: courtesy Richard Bell

There is an attempt to distance ourselves from the punitive actions of the Howard government by constructing an ‘other space’ in which other presents and futures are possible. This is a space I call ‘xenotopia’, a kind of striated not here but here. It is an imagined and unknowable place for/of others or strangers that sweeps across the spaces of alternative (or ethical) community, exile and containment. Curator and writer Djon Mundine observed that white Australia selectively claims, perhaps consumes, Aboriginal public figures as its own – ‘our Cathy [Freeman]’, but not ‘our Richard [Bell]’.12 Owning, claiming and consuming Indigenous culture, land and peoples is the stuff of assimilation, of permitting entry on provisional grounds. Goward wanted to make Bell accountable. In her response to Bell’s slogan, she said “it’s got to be understood that the law and cultural standards have to be upheld by everyone in Australia, regardless of colour and creed.”13 But what does it mean for Indigenous people to be un/Australian? Having flaunted the rules in such an unpalatable and unassimilable manner, having exposed trenchant double standards, Bell apparently sealed his unAustralianness, which is meaningless in Bell’s oeuvre. As Morgan Thomas explains of Bell’s 2002 work Worth Exploring?, the overriding factor is the “illegality of the white occupation of Australia, taking this illegality as the premise for the claim that everything subsequent to this occupation is ultra vires (illegal, outside the law) and drawing the consequence that all non-Aboriginal Australians must be counted as criminals and all Aboriginal people recognised as the victims of crime”.14 In being outside the law, all non-Aboriginal – or unAboriginal people – are thoroughly implicated.15

The provisions of the anti-terror laws shift the emphasis, bringing

this question of nationalism into sharper view. When I started writing,

the controversies and the questions they evoked, while important,

existed in a less urgent frame. The acts and utterances of these

artists were not offences potentially punishable by imprisonment. The

war against terror hadn’t yet inured as a war against this country’s

citizens. The intricate coupling of security and fear makes this

inflation of hostility towards unAustralians more compelling – they are destroying our

way of life, a kind of mobilisation against and weeding out of the

enemy within. When initially drafted, the anti-terror provisions for

‘seditious intent’ had the potential to ensnare artists whose work

might be construed as “bringing the Sovereign into hatred and

contempt”, “urging disaffection against the constitution, the

Government of the Commonwealth, either House of Parliament” and

“promoting feelings of ill-will or hostility between different groups

so as to threaten the peace, order and good governance of the

Commonwealth”. “Recklessness” was also factored into several sedition

provisions. While there was some provision for acts done in “good

faith”, the greatest threat to artists would have been interpretative

acts arising from distrust of images or proffer literalism as the

measure of image. Artists and art, in this era of fundamentalism and

literalism, are easy targets with the good faith provisions not

acknowledging artists or artworks.

In this light, Escape from Woomera is particularly relevant given that it is an artist devised computer game in which players take on the roles of escaping detention centre inmates. Mandatory detention of refugees and asylum seekers is regarded as integral to national security. It is one of the most divisive issues in the Australian polity. One of the criticisms of the game by Ruddock was that it encouraged participation in illegal activities. However, this reaction seems like an arbitrary ruse given that illegal activities are also featured in best-selling games, such as Grand Theft Auto III, which involve car theft, violence and murder. Under the legislation, artists could be vulnerable when criticising the issues, government and politics of the day. According to Ruddock, currently Attorney-General, the crux is now, with some qualification of sedition included in the law, the urging of hostility or violence towards the government.16 How might we legally define urging. Given that I am discussing situations where representing an act is regarded as tantamount to urging that act, is urging an act the same as doing it or, worse, does representing an act equate to doing it? Applying the distinction of J.L. Austin, language (and, arguably, any representation) is not only used to state facts, but also to perform actions. Austin identifies ‘performatives’ whereby “the issuing of the utterance is the performing of the action – it is not normally thought of as just saying something”.17 How do we distinguish the enunciative and the performative in alleged acts of sedition predicated on urging?

truth or dare

In the onslaught of literalism, the open-endedness of interpretation and imagination is unceremoniously severed. Wendy Steiner argues that the arts have been made vulnerable because the virtuality of the image has been lost to literalism and that this feeds uncertainties about visual representation, thinking and ideas. This virtual realm, according to Steiner, suggests that art is “neither identical to reality nor isolated from it, but … tied to the world by acts of interpretation”.18 Says Steiner, “in this literalism, this fundamentalist scare story, the artwork is not invested by its audience with a virtual power, but possesses, itself, a power that we cannot control … we must reconceive the power of art as neither a formalist enthrallment nor a fundamentalist nightmare”.19

We now live in a world saturated by media and images and, as David Hickey stresses, “works of art in this culture do not have determinate or discoverable meanings”.20 Partly due to the unstable realm of images and subjective nature of interpretation, Steiner also says that expertise in the arts, whether as artist or critic, is resisted, often buried in a mire of anti-intellectualism. The message is often lost – to represent something is not the same as advocating for it. Yet, as Dubin notes, since the 1960s, “the burden of explaining this increasingly complex art scene has fallen to contemporary art critics”.21 Steiner observes, “outside of journalism, there is no sphere in which aesthetic value and pleasure are discussed with any regularity”22 – at least not on a mass scale. However, the media23 tend to blow hot and cold about art and arts issues, regularly erupting with outrage and miscomprehension over funding outcomes and, in some instances, dogging artists who have received arts grants in a country where incomes derived from artistic practice are about 15% of the nation’s average wage.

How well equipped are we to deal with and live with this virtual world of art when, as one art critic claimed, our visual education ends by the age of seven? As Steiner argues:

With the best of intentions, professors teach contemporary art with all its humor, paradox, and occasional provocation, hoping to promote pleasure and an understanding of the world through an understanding of a crucial part of it – representation … But for opponents of the liberal academy, complexity and ambiguity are merely mystifications, and contemporary art in fact compounds social disorder. The world’s ills should be overcome instead by the enforcement of hierarchies and systems inherited from the past, with art fulfilling its social mission by bolstering and justifying these systems.24

who said that?

Historically, sedition laws have been used as tools of arbitrary persecution and oppression. While Australia is signatory to many international human rights conventions and the Commonwealth and state governments have introduced legislation that confers some rights of equality, this country has stopped short of introducing a Bill of Rights as a constitutional amendment. In Australia, human rights are undecided at the level of legislature and government. Rights of free speech do not have any legal or constitutional foundation in this country – they are a matter of principle. Despite the problematic and universalising nature of rights discourse, under the current government, the lack of these provisions is sorely felt – tenuous claim to inalienable rights and curtailed recourse in the event of incursion. According to Amnesty International, the proposed anti-terror laws have the effect of undermining the liberal democratic values they are designed to protect. When issues of freedom of speech and the right to dissent are weighed against sedition in the context of Australian democracy, a discourse of human rights as it applies to civil liberties and artistic freedom is generally upheld. The Australian reported “our parliamentary democracy is underpinned by a free press and the right of citizens to tell the government of the day that it is wrong.”25 But on what legislative grounds?

By late November 2005, a Senate committee had recommended that the sedition provisions of the proposed anti-terror law be scrapped but the government refused to budge, although pledged to review the legislation after it was enacted. The Australian reported, additional to ‘good faith’, “ sedition laws will contain a new ‘public interest’ defence to reflect the concerns of media outlets and Coalition MPs that the provisions could harm free speech”.26 In this respect, the change does little to protect artists. Also, this attempt at qualification seems to define one set of woolly terms with another – what is the “public interest”? The good faith defence is not applicable if a person has urged force or violence. While calls to review the legislation persist as does a view that sedition laws are unwarranted,27 Ruddock said those provisions are “designed to protect the community from those who would abuse our democratic values and threaten our harmonious and tolerant society”.28 More importantly the government has rapidly legislated for the removal and erosion of rights while consistently manipulated and backpeddled on constitutional reform issues such as referenda on a Bill of Rights and republic. How does the government, given the distrustful demeanour of the present political environment, countenance its own actions as urgings towards civil disobedience and hostility? Legislating representation, the effective outcome of sedition laws, is fraught given that representation is comprised of thought experiments. There are few attempts to engender broader understanding of the instability of art and image in our society, and some of the media attention art receives evinces this instability. Images are pervasive and our visual literacy is constantly under challenge in our world, calling on ever-refined abilities to differentiate real from virtual and to comprehend their points of crossover.

There is a view I hear from time to time that art does nothing and that it changes nothing. However, this view is exposed as fallacious when art is attacked, usually on spurious grounds, and when commentators of various political persuasions consider the ramifications of regulating or outlawing the thought, dialogue and pleasure that come of art. At these times, we become acutely aware of the power of the symbolic and the ways that art provokes and produces. There is something incommensurable about art, a kind of uncertainty that promises nothing. It’s the sort of uncertainty that doesn’t sit well in the fear infested drives of literalism and fundamentalism. If ministerial, media and public responses to dissent and difference, such as garrulously conjured by Escape from Woomera and Richard Bell are any indication, then both the ability to differentiate and willingness to negotiate the real and virtual is still remote. I’m not arguing that every decision made in or about the arts should pass quietly by without any scrutiny or debate. It is through these discussions we might come to reiterate the value of art and virtuality. However, the confused and incendiary interpretations of images and intent have fuelled controversies and calls to deal with those two offenders, as transgressors of the racialised boundaries around the construction of nation, in an overtly castigatory manner.

Only a few years past, it’s not a leap to speculate about the deteriorated circumstances in which these representations can be regarded as seditious or dangerously subversive.29 Could we have surmised in 2003 that artists would be campaigning to defend fundamental civil liberties? Since then, Escape from Woomera has been exhibited without further incident and Richard Bell continues to produce and sell work. While there are innumerable observations to be made and conclusions to be drawn from these two art controversies, this essay serves to situate and reflect on the particularly problematised nature of representation now. In those moments of intensity, we witnessed a knotted conflation of issues and responses that shine the spotlight on arts funding, art markets, virtuality, aesthetics, race and gender issues, public policy, nationalism, citizenship and more. This is the sort of rippling that should move us to ask seriously probing questions about the vitality of our democracy, national identity and public culture. Quite possibly it’s only out of art, as a kind of ‘thought space’ riddled with dubiety, that this foment is likely; where the virtual and the real demonstrate their separate-togetherness, their permeability. It is not a simple binary – we are thoroughly enmeshed – the virtual is not only bound to the real, but the real also finds its articulation in the virtual. In the unfurling of these two controversies, these artworks were received in ways that demonstrate their significance and also their pleasure, highlighting one of the many roles of art in the stark reality of these times. These artworks encourage us to feel, to see and to play – to know the kind of pleasure that comes of provocative visual thinking, reckless irreverence and quick-witted urges.

NOTES

1 Escape from Woomera website http://www.escapefromwoomera.org

2 Steven C. Dubin, Arresting Images: Impolitic art and uncivil actions. New York: Routledge. 1992. 6

3 Sean Nicholls, “Escape game wires the minister”. Sydney Morning Herald. 30 August 2003. 1

4 ibid.

5

Much of Bell’s work is comprised of uncompromising statements including

“I AM NOT SORRY”, “I AM HUMILIATED” and “A LIE FOR A LIE AND A MYTH FOR

A MYTH”. The texts can appear as paintings, t-shirts and badges.

6 Louise Martin-Chew, “Brush with Activism”. Australian. 28 August 2005. 13

7 Matt Adams: Blast Theory, Adelaide Thinkers in Residence Public Lecture. Adelaide Town Hall. 16 March 2004.

8

John Howard interviewed on 3AW by Neil Mitchell. 22 August 2003.

Accessed 5 December 2005.

http://www.pm.gov.au/news/interviews/Interview445.html

9 Bell’s Theorem

can be read at http://www.kooriweb.org/foley/great/art/bell.html and

other texts about Bell’s work at

http://www.kooriweb.org/foley/great/art/rbell.html

10 Joseph Pugliese, “To be unAustralian – is it now a badge of honour?”, Macquarie University News, May 2005, Sydney. 12

11 ibid.

12 Djon Mundine. “White face/blak mask”. Artlink. Vol 25 No 3. Accessed 3 December 2005. http://www.artlink.com.au/articles.cfm?id=2007

13 Christine Jackman, ‘Goward demands “sorry” for T-shirt’. Australian. 22 August 2003. 3

14 Morgan Thomas, “Who’s Dreaming Now?”, 2003. Accessed 8 December 2005. http://www.kooriweb.org/foley/great/art/article2.html

15

Because Goward and others took Bell’s comment literally and because

there were attempts to summarily invert the statement through protests

like ‘what if a white man said this about black women?’ ie the shoe was

on the other foot, there was failure to extend the analysis to see the

kind of political position and borders of nation/country that Bell is

demarcating in his works.

16 Phillip Ruddock interviewed by Tracy Grimshaw, Today,

Channel 9. Brisbane. 7.15am, 7 December 2005. The law will say that: “A

person commits an offence if the person urges another person to

overthrow by force or violence: (a) the Constitution; or (b) the

government of the commonwealth, a state or a territory; or (c) the

lawful authority of the government of the commonwealth.”

17 J.L. Austin, How to Do Things with Words, J.O. Urmson, ed. New York: Oxford University Press. 1962. 6-7

18 Wendy Steiner, The Scandal of Pleasure: Art in an age of fundamentalism. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. 1995. 8

19 ibid. 82

20 David Hickey, “Simple Hearts: Still Writing Talks”, Art Issues, March/April, 1991. 11

21 Dubin. Op.cit. 23

Steiner. 7

22 While it’s primarily print media that sustains arts rounds and reporters, in the circumstances of Richard Bell and Escape from Woomera,

there was significant electronic media attention including talkback

radio. There is strong indication that arts coverage, ranging from

integration of arts reporting to specialist programming/rounds across

the media, is gradually decreasing. This is not because arts reporting

has been integrated into other news sections .

23 Steiner. op.cit., 5

24 “Sedition laws won't curb the right to criticise Queen and country”, Australian.

8 December 2005. Accessed 8 December 2005.

http://www.theaustralian.news.com.au/common/story_page/0,5744,17494211%255E7582,00.html

25 Samantha Maiden, ‘Sedition law changes back free speech’. Australian, 1 December 2005. Accessed 1 December 2005. http://www.news.com.au/story/0,10117,17421270-421,00.html

26 See Freedom for Expression weblog at http://ozsedition.blogspot.com/

27 cited by Thomas Kenneally, “Alert and Alarmed: art under fire”. Sydney Morning Herald.

29 November 2005. Accessed 3 December 2005.

http://www.smh.com.au/news/arts/alert-and-alarmed-art-under-fire/2005/11/28/1133026405834.html

28

There have been several incidents of late where political artworks have

attracted unwarranted attack, destruction or removal. For example, on

11 November 2005, the ABC reported on an exhibition of portraits by

Michael Agzarian at the Wagga Wagga Art Gallery. The portraits of

politicians with their lips sewn together had attracted a treason

complaint which was investigated by the Department of Communications,

Information Technology and the Arts. 11 November 2005. Accessed 7

December 2005.

http://www.abc.net.au/news/newsitems/200511/s1504405.htm. Further the Australian reported

that Wagga Wagga Art Gallery received phone calls from the Department

of Communications, Information Technology and the Arts inquiring about

whether the Agzarian exhibition was federally funded. Art gallery

'pressured over painting'. Australian. 8 December 2005.

Accessed 8 December 2005.

http://www.theaustralian.news.com.au/common/story_page/0,5744,17499345%255E29277,00.html.

For assistance with this essay, I am grateful for the insights of JMJA and MS. Images generously provided by the artists. Thank you RB and EFW Collective.